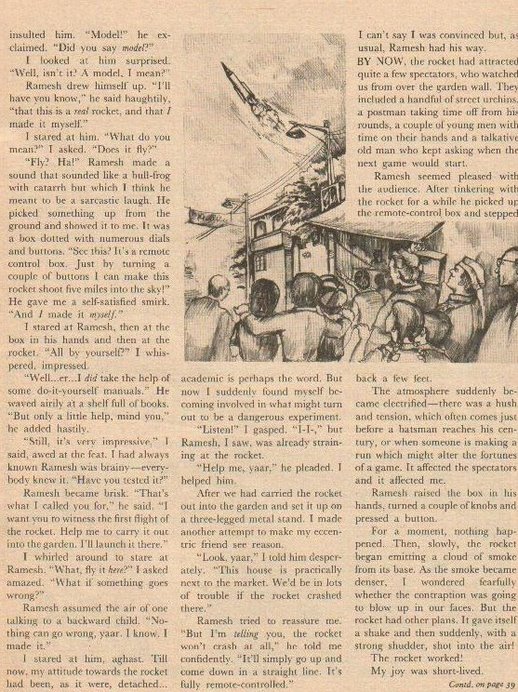

It all started innocently enough. Ramesh and I were walking home from school one sunny afternoon. It was a pleasant day, so we’d decided to walk back rather than travel in a stuffy, over-crowded bus. The next day was a school holiday and we were in no hurry. The streets we were now walking through were almost unknown to us - only part of swiftly changing scenery usually viewed through bus windows. Today Ramesh, a born explorer, was eager as ever to investigate this new and unvisited terrain.

Which perhaps explains what happened next.

We were walking through a small market when, suddenly, Ramesh halted and pointed to a shop in front of us. “Look!” he exclaimed, his spectacles glinting excitedly. “A junk shop!”

It was a small, nondescript shop, rather shabby to look at, with one dirty front window behind which were cluttered all sorts of second-hand articles.

“So what?” I asked, a little irritably, for I knew what was coming next. “You’ll find one such shop tucked away in every small market.”

But I was wasting my breath, of course. Ramesh’s unbridled curiosity would never let him pass by a junk shop without exploring its contents. Even as I was speaking, Ramesh had started moving towards the shop like a blood-hound hot on a scent. I could only follow.

The dim light inside of the shop did nothing to raise my spirits. In addition to being very dirty, it was literally overflowing with junk of all kinds. Ramesh, of course, was in his element. Without bothering even to glance at the man standing behind a small counter at the back of the shop, he began pottering here and there with a questing look on his face, like an income-tax officer assessing the value of a film-star’s property.

There was enough junk in the shop to keep Ramesh busy for hours. Having nothing better to do, I began to look closely at some of the stuff lying around. Slowly my interest began to mount. There were oil lamps, a bronze dancing girl, pots and caskets, an old magnifying glass, ornamental swords and lots of mouldy old coins.

Some of Ramesh’s excitement was beginning to rub off on me when I suddenly heard a shout and, turning my head, I saw my friend, his spectacles slightly askew, staring down at something in his hands. Looking up, he excitedly signaled me to come over to him.

The object in Ramesh’s hands was a large, slightly chipped, but nonetheless exquisitely carved, wooden box. Or so it seemed to me at first sight. But, on closer examination, it actually turned out to be miniature chest-of-drawers. Slowly, very carefully, Ramesh pulled out one drawer after the other. There were six of them.

“Beautiful, isn’t it?” whispered Ramesh, staring down lovingly at the chest-of-drawers.

“Yes,” I replied. “Even though the wood is slightly chipped and rough-looking.”

“Oh, the roughness is no problem,” said Ramesh airily. “A bit of polish will smoothen that out.”

“Perhaps,” I said, rather doubtfully. And then the full significance of his statement struck me. I stared at Ramesh. “Are you planning to buy this box?” I exclaimed.

“Yes,” he replied. “Why not?”

“But-but it might be very expensive!”

Ramesh shook his head knowledgeably, “No it won’t,” he said confidently “This chest-of-drawers is apparently not very valuable and even if it is, the shopkeeper evidently doesn’t know it. Otherwise, the box would never have been kept so carelessly among all this junk.” Which was all very true, of course.

Before I could reply to this piece of logic, Ramesh had approached the man behind the counter. The shopkeeper turned out to be a wizened old man, as small and shabby as the shop. As Ramesh had predicted, the price of the chest-of-drawers was low. In fact, the shopkeeper had some difficulty in recognizing the box at first. But Ramesh was a skillful bargainer and he managed to bring the price down to almost half the original amount. Even then he did not have enough money and I had to pool in.

As we wandered homewards, Ramesh continued to fiddle with miniature chest-of-drawers, though, for the life of me, I failed to see what there was in our recent purchase to be so curious about.

I was soon to find out.

Barely a few minutes after we had left the junk shop Ramesh suddenly turned to face me, evidently excited at something.

“Look!” he said breathlessly. “I’ve been going over this box carefully and I think there’s more to this chest-of-drawers than we we’ve been able to see so far!”

This was Greek to me. “What do you mean?” I asked suspiciously.

“Here, look!” Ramesh came to a halt in the middle of the pavement, forcing me to do the same. He raised the chest-of-drawers until it was level with my face. “See this carved section between the lowest drawer and the base? Doesn’t it sound slightly hollow?” I nodded. Ramesh lowered the miniature chest-of-drawers. His face was flushed. “Perhaps there’s a hidden compartment at the base!” he exclaimed.

I slowly scratched my head. Ramesh certainly knew how to be convincing. “So what do we do now?” I asked.

Ramesh gave a quick look around him. “See that restaurant over there?” he asked. “Let’s go in and have a soft drink each while we examine this box more carefully. Perhaps we might find a hidden lever or something!”

As usual, Ramesh was already on his way to the restaurant before I could reply. Meekly, I followed.

At the restaurant, we examined the miniature chest-of-drawers closely. The box itself was about eight inches in height with six small drawers spaced at one inch intervals. At the base of the chest-of-drawers was a one-and-a-half inch wide carved portion which surrounded the box like a belt. The carvings were of flowers. As Ramesh had pointed out, the carved portion did sound slightly hollow when he tapped it.

Ramesh ran his hand over the carved portion. “If there is a secret compartment,” he said excitedly, “then the catch must be hidden in the carvings!” He looked wistfully at the chest-of-drawers. “If only I can find it!”

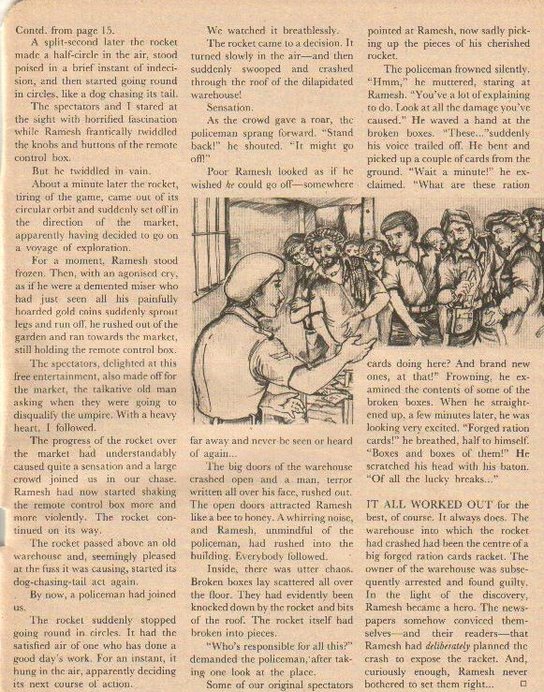

Of course, he found it. With his patience and determination, it was only a matter of time. While I sipped my soft drink, Ramesh carefully probed each section of the carvings with his fingers. It was when he was half-way round the base that he found it. He had pressed the centre of a large carved flower and was about to pass on when, suddenly, with a small click, a seventh drawer slid out from the base of the box!

Time sometimes does seem to stand still. It did then. Ramesh and I stared at the open drawer for a long while, scarcely conscious of our surroundings. It wasn’t just the fact that we had discovered a secret compartment that held us speechless - though that was exciting enough. What made our eyes shoot out of their sockets and a tingle run up our spines was a small, yellow envelope which lay exposed in the bottom of the secret drawer.

Ramesh was the first to move. Slowly, like a rheumatic patient, he raised a shaking hand and carefully lifted the envelope out of the drawer. Then, even more slowly, he raised the flap of the envelope - it was not gummed - and peered inside. When he raised his eyes again, there was a puzzled look on his face. “It’s empty,” he whispered “There’s nothing in it!”

It was not immediately that I replied. Ramesh had merely been looking inside the envelope. I had seen something on the envelope that had affected me like a thunderbolt. If my eyes were to be believed, Ramesh and I had just made a very valuable discovery. A discovery worth, perhaps, many many thousands of rupees!

Ramesh was looking at me in a puzzled manner. “What’s up?” he asked. “Why are you looking like a stuffed pig?”

My voice, when I was able to speak, was husky. If a throat specialist had been present, he would have given me a sharp look, expecting a new patient.

"The stamp!” I breathed hoarsely. “Look at the stamp!”

Ramesh stared at me in amazement. Then he glanced down at the envelope in his hand – and stiffened. When he raised his eyes again this time, they were shining. “A Sirijpur ‘Royal Head!’” he whispered unbelievingly. “Yes,” I said, “a Sirijpur ‘Royal Head’.”

Ramesh and I, both avid stamp collectors, had had no difficulty in recognizing the stamp on the yellow envelope. It was a green and white stamp issued by the Princely State of Sirijpur in the last decade of the nineteenth century. It was one of the earliest Indian stamps ever printed and,therefore, very valuable.

Our soft drinks forgotten, Ramesh and I excitedly examined the envelope. It was obviously very old. The paper was hard and yellowish. We could not make out the address on the front of the envelope because the ink had become faded and illegible. The same was true of the postmark. But there could be no mistaking the stamp. It was, without doubt, a Sirijpur ‘Royal Head’!

We could hardly control our excitement. “It must be worth lots and lots of money,” I said. “How much, do you think?”

“I don’t know,” replied Ramesh thoughtfully. “But my father will know. Come, let’s go and ask him.”

We quickly paid for out soft drinks and, having first carefully placed the envelope back in the secret compartment, left the restaurant. This time we did not dawdle on the way.

Neither did we dawdle after reaching Ramesh’s house. We found Ramesh’s father in the drawing-room and immediately placed the miniature chest-of-drawers on a table in front of him. Ramesh, collapsing on a stool, pressed the centre of the carved flower and the secret drawer slid out. Picking up the envelope from the drawer, Ramesh presented it to his father. “Look at the stamp,” he said briefly. “Isn’t it a Sirijpur ‘Royal Head’?”

Ramesh’s father had not been Ramesh’s father for so many years without having learnt to take surprises in his stride. Another man might have been confused by this sudden bombardment of secret compartments, old envelopes and rare stamps. Ramesh’s father merely adjusted his spectacles and stared at the envelope. “You’re right,” he said. “It is a Sirijpur ‘Royal Head’.”

Ramesh jumped up excitedly. “How much is it worth?” he asked.

His father extended his hand for the stamp. “Let me see it,” he said.

Ramesh’s father looked at the stamp carefully for sometime. Then he told us the verdict. “I’m very sorry,” he said, “but I’m afraid this stamp isn’t really worth very much.”

“But why, sir?” I asked, surprised. “I thought a Sirijpur ‘Royal Head’ was valuable – it being an old and rare stamp.”

“It all depends on the condition of the stamp,” Ramesh’s father told us. “A good specimen would be worth several thousand rupees, but I’m afraid this one is not a particularly good one. You see, being imperforate, that is, having no perforations on the margin, the stamp had to be cut from the original sheet with a pair of scissors. Good specimens need a nice margin all round, but if you examine this stamp, you’ll notice that a tiny corner of the design has been snipped off. This reduces the value quite a lot.” He handed the envelope back to a stunned Ramesh. “But don’t look so disappointed. Even a really good specimen might not be worth a fortune, so you haven’t lost all that much. Anyway, it really is a Sirijpur ‘Royal Head’, which is more than what most schoolboys are able to own.”

He was right, of course. Nevertheless, our disappointment was great.

We know not what awaits us round the corner, runs the well-known proverb, and the hand that counteth its chickens before they be hatched oft-times doth but step on the banana skin. Sitting in Ramesh’s room five minutes later, and thinking over the day’s events, I realized the truth of this.

“We shouldn’t have counted our chickens before they were hatched, like the proverb says,” I told my friend, shaking my head wisely.

“Shut up,” said Ramesh.

I was about to give a heated reply to this, when I noticed that Ramesh’s thoughts were elsewhere. He had taken out the envelope from the secret drawer and was staring at it in a peculiar manner.

“What’s up?” I asked curiously. Ramesh looked at me. The glint in his spectacles told me that my friend’s curiosity was once again working overtime. “Have you ever stopped to wonder,” he asked me slowly, “why the envelope was hidden in the secret drawer in the first place?”

I was ready for this. “Well, it’s obvious that the person who hid the envelope must have thought the stamp was valuable, the same as we did.”

But Ramesh was not to be put off so easily. “I’m not so sure…,” he said thoughtfully. He looked down at the envelope in his hand. “Even if that person thought the stamp was valuable, then why hide it? Why not sell it, or stick it in a stamp album? Why hide it?”

He had me there. I had no ready answer.

Ramesh, whose suspicions were growing like flowers in spring, carefully put down the envelope and, from a nearby drawer, took out a magnifying glass. “There must be something special about the envelope that makes it valuable enough to hide,” he explained to me. “I’m going to find out what it is,” he continued determinedly.

I walked over to where Ramesh was sitting and stood behind him. Ramesh picked up the envelope again and, as I stared over his shoulder, he began to go over it once more, inch by inch. “I’m convinced,” he told me, “that somehow we’ve been missing something that’s been staring us in the face all the time.” The fiasco of the Sirijpur ‘Royal Head’ had evidently not dampened Ramesh’s habitual curiosity.

Together, we attempted – unsuccessfully – to decipher the illegible address on the envelope… Ramesh examined the address under the magnifying glass… he put his magnifying glass over the postmark and the stamp.

Then Ramesh suddenly snapped his fingers.

He sprang up from his chair, with the alacrity of a leopard that had sat down on an anthill by mistake, clutching the envelope in his hand, his head nearly crashing into my jaw. “We’re going to the kitchen,” he told me briefly, and was out of the room before I could react to this startling announcement.

By the time I had made my way to the kitchen, considerably puzzled by Ramesh’s strange behaviour, my friend had already put a kettle of water on to boil. The strain had evidently been too much for him. “I – I don’t think I’ll have any tea, thank you,” I told him politely, having read somewhere that the best way to deal with lunatics is to humour them.

Ramesh gave no reply. He waited impatiently, his face flushed, until the kettle began to boil. Then slowly lifting his hand, he held the envelope in the steam and very carefully peeled off the stamp.

He uttered a shout of triumph.

With one bound, I was at Ramesh’s side. My friend was staring down at the back of the stamp he had just peeled off. I too stared at the back of the stamp. And as I did so, my head began to swim. A message, in closely-packed, microscopic handwriting, had been hidden under the stamp!

I blinked, half expecting the words to disappear. They didn’t. Ramesh sat down on a nearby stool and studied the message under his magnifying glass. Then he gave a low whistle. “I wonder what my father will have to say about this…,” he said slowly.

Ramesh’s father had a lot to say about the discovery. In fact, after only one glance at the message through Ramesh’s magnifying glass, he became so excited that he immediately called over some scholar friends of his to have a look at the find. They confirmed the great value of the discovery. What Ramesh had discovered at the back of the stamp was a secret message sent by the British Political Resident of Sirijpur State to his colleague in the neighbouring Princely State at the end of the nineteenth century. The message shed new light on involvement of the then colonial British rulers of India in the affair of the then Raja (King) of Sirijpur, who gave up his throne in favour of his nephew in 1899. Although the British were suspected of having put pressure on the Raja (who they felt had ties with Indian feedom fighters) to abdicate, no proof of this was ever found. The secret message Ramesh had discovered was the first concrete evidence of their involvement. It thus had great historical and antique value.

Not long after, a museum bought the envelope and stamp, paying a lot of money for it. Ramesh insisted on sharing the money with me, since I had contributed towards buying the miniature chest-of-drawers which started it all. Nevertheless, it was only due to Ramesh’s great curiosity that the discovery was made. And Ramesh, true to form, is still not content. He now wants to find out how the envelope came to be hidden in the miniature chest-of-drawers in the first place.

We are planning to re-visit the junk shop!

Which perhaps explains what happened next.

We were walking through a small market when, suddenly, Ramesh halted and pointed to a shop in front of us. “Look!” he exclaimed, his spectacles glinting excitedly. “A junk shop!”

It was a small, nondescript shop, rather shabby to look at, with one dirty front window behind which were cluttered all sorts of second-hand articles.

“So what?” I asked, a little irritably, for I knew what was coming next. “You’ll find one such shop tucked away in every small market.”

But I was wasting my breath, of course. Ramesh’s unbridled curiosity would never let him pass by a junk shop without exploring its contents. Even as I was speaking, Ramesh had started moving towards the shop like a blood-hound hot on a scent. I could only follow.

The dim light inside of the shop did nothing to raise my spirits. In addition to being very dirty, it was literally overflowing with junk of all kinds. Ramesh, of course, was in his element. Without bothering even to glance at the man standing behind a small counter at the back of the shop, he began pottering here and there with a questing look on his face, like an income-tax officer assessing the value of a film-star’s property.

There was enough junk in the shop to keep Ramesh busy for hours. Having nothing better to do, I began to look closely at some of the stuff lying around. Slowly my interest began to mount. There were oil lamps, a bronze dancing girl, pots and caskets, an old magnifying glass, ornamental swords and lots of mouldy old coins.

Some of Ramesh’s excitement was beginning to rub off on me when I suddenly heard a shout and, turning my head, I saw my friend, his spectacles slightly askew, staring down at something in his hands. Looking up, he excitedly signaled me to come over to him.

The object in Ramesh’s hands was a large, slightly chipped, but nonetheless exquisitely carved, wooden box. Or so it seemed to me at first sight. But, on closer examination, it actually turned out to be miniature chest-of-drawers. Slowly, very carefully, Ramesh pulled out one drawer after the other. There were six of them.

“Beautiful, isn’t it?” whispered Ramesh, staring down lovingly at the chest-of-drawers.

“Yes,” I replied. “Even though the wood is slightly chipped and rough-looking.”

“Oh, the roughness is no problem,” said Ramesh airily. “A bit of polish will smoothen that out.”

“Perhaps,” I said, rather doubtfully. And then the full significance of his statement struck me. I stared at Ramesh. “Are you planning to buy this box?” I exclaimed.

“Yes,” he replied. “Why not?”

“But-but it might be very expensive!”

Ramesh shook his head knowledgeably, “No it won’t,” he said confidently “This chest-of-drawers is apparently not very valuable and even if it is, the shopkeeper evidently doesn’t know it. Otherwise, the box would never have been kept so carelessly among all this junk.” Which was all very true, of course.

Before I could reply to this piece of logic, Ramesh had approached the man behind the counter. The shopkeeper turned out to be a wizened old man, as small and shabby as the shop. As Ramesh had predicted, the price of the chest-of-drawers was low. In fact, the shopkeeper had some difficulty in recognizing the box at first. But Ramesh was a skillful bargainer and he managed to bring the price down to almost half the original amount. Even then he did not have enough money and I had to pool in.

As we wandered homewards, Ramesh continued to fiddle with miniature chest-of-drawers, though, for the life of me, I failed to see what there was in our recent purchase to be so curious about.

I was soon to find out.

Barely a few minutes after we had left the junk shop Ramesh suddenly turned to face me, evidently excited at something.

“Look!” he said breathlessly. “I’ve been going over this box carefully and I think there’s more to this chest-of-drawers than we we’ve been able to see so far!”

This was Greek to me. “What do you mean?” I asked suspiciously.

“Here, look!” Ramesh came to a halt in the middle of the pavement, forcing me to do the same. He raised the chest-of-drawers until it was level with my face. “See this carved section between the lowest drawer and the base? Doesn’t it sound slightly hollow?” I nodded. Ramesh lowered the miniature chest-of-drawers. His face was flushed. “Perhaps there’s a hidden compartment at the base!” he exclaimed.

I slowly scratched my head. Ramesh certainly knew how to be convincing. “So what do we do now?” I asked.

Ramesh gave a quick look around him. “See that restaurant over there?” he asked. “Let’s go in and have a soft drink each while we examine this box more carefully. Perhaps we might find a hidden lever or something!”

As usual, Ramesh was already on his way to the restaurant before I could reply. Meekly, I followed.

At the restaurant, we examined the miniature chest-of-drawers closely. The box itself was about eight inches in height with six small drawers spaced at one inch intervals. At the base of the chest-of-drawers was a one-and-a-half inch wide carved portion which surrounded the box like a belt. The carvings were of flowers. As Ramesh had pointed out, the carved portion did sound slightly hollow when he tapped it.

Ramesh ran his hand over the carved portion. “If there is a secret compartment,” he said excitedly, “then the catch must be hidden in the carvings!” He looked wistfully at the chest-of-drawers. “If only I can find it!”

Of course, he found it. With his patience and determination, it was only a matter of time. While I sipped my soft drink, Ramesh carefully probed each section of the carvings with his fingers. It was when he was half-way round the base that he found it. He had pressed the centre of a large carved flower and was about to pass on when, suddenly, with a small click, a seventh drawer slid out from the base of the box!

Time sometimes does seem to stand still. It did then. Ramesh and I stared at the open drawer for a long while, scarcely conscious of our surroundings. It wasn’t just the fact that we had discovered a secret compartment that held us speechless - though that was exciting enough. What made our eyes shoot out of their sockets and a tingle run up our spines was a small, yellow envelope which lay exposed in the bottom of the secret drawer.

Ramesh was the first to move. Slowly, like a rheumatic patient, he raised a shaking hand and carefully lifted the envelope out of the drawer. Then, even more slowly, he raised the flap of the envelope - it was not gummed - and peered inside. When he raised his eyes again, there was a puzzled look on his face. “It’s empty,” he whispered “There’s nothing in it!”

It was not immediately that I replied. Ramesh had merely been looking inside the envelope. I had seen something on the envelope that had affected me like a thunderbolt. If my eyes were to be believed, Ramesh and I had just made a very valuable discovery. A discovery worth, perhaps, many many thousands of rupees!

Ramesh was looking at me in a puzzled manner. “What’s up?” he asked. “Why are you looking like a stuffed pig?”

My voice, when I was able to speak, was husky. If a throat specialist had been present, he would have given me a sharp look, expecting a new patient.

"The stamp!” I breathed hoarsely. “Look at the stamp!”

Ramesh stared at me in amazement. Then he glanced down at the envelope in his hand – and stiffened. When he raised his eyes again this time, they were shining. “A Sirijpur ‘Royal Head!’” he whispered unbelievingly. “Yes,” I said, “a Sirijpur ‘Royal Head’.”

Ramesh and I, both avid stamp collectors, had had no difficulty in recognizing the stamp on the yellow envelope. It was a green and white stamp issued by the Princely State of Sirijpur in the last decade of the nineteenth century. It was one of the earliest Indian stamps ever printed and,therefore, very valuable.

Our soft drinks forgotten, Ramesh and I excitedly examined the envelope. It was obviously very old. The paper was hard and yellowish. We could not make out the address on the front of the envelope because the ink had become faded and illegible. The same was true of the postmark. But there could be no mistaking the stamp. It was, without doubt, a Sirijpur ‘Royal Head’!

We could hardly control our excitement. “It must be worth lots and lots of money,” I said. “How much, do you think?”

“I don’t know,” replied Ramesh thoughtfully. “But my father will know. Come, let’s go and ask him.”

We quickly paid for out soft drinks and, having first carefully placed the envelope back in the secret compartment, left the restaurant. This time we did not dawdle on the way.

Neither did we dawdle after reaching Ramesh’s house. We found Ramesh’s father in the drawing-room and immediately placed the miniature chest-of-drawers on a table in front of him. Ramesh, collapsing on a stool, pressed the centre of the carved flower and the secret drawer slid out. Picking up the envelope from the drawer, Ramesh presented it to his father. “Look at the stamp,” he said briefly. “Isn’t it a Sirijpur ‘Royal Head’?”

Ramesh’s father had not been Ramesh’s father for so many years without having learnt to take surprises in his stride. Another man might have been confused by this sudden bombardment of secret compartments, old envelopes and rare stamps. Ramesh’s father merely adjusted his spectacles and stared at the envelope. “You’re right,” he said. “It is a Sirijpur ‘Royal Head’.”

Ramesh jumped up excitedly. “How much is it worth?” he asked.

His father extended his hand for the stamp. “Let me see it,” he said.

Ramesh’s father looked at the stamp carefully for sometime. Then he told us the verdict. “I’m very sorry,” he said, “but I’m afraid this stamp isn’t really worth very much.”

“But why, sir?” I asked, surprised. “I thought a Sirijpur ‘Royal Head’ was valuable – it being an old and rare stamp.”

“It all depends on the condition of the stamp,” Ramesh’s father told us. “A good specimen would be worth several thousand rupees, but I’m afraid this one is not a particularly good one. You see, being imperforate, that is, having no perforations on the margin, the stamp had to be cut from the original sheet with a pair of scissors. Good specimens need a nice margin all round, but if you examine this stamp, you’ll notice that a tiny corner of the design has been snipped off. This reduces the value quite a lot.” He handed the envelope back to a stunned Ramesh. “But don’t look so disappointed. Even a really good specimen might not be worth a fortune, so you haven’t lost all that much. Anyway, it really is a Sirijpur ‘Royal Head’, which is more than what most schoolboys are able to own.”

He was right, of course. Nevertheless, our disappointment was great.

We know not what awaits us round the corner, runs the well-known proverb, and the hand that counteth its chickens before they be hatched oft-times doth but step on the banana skin. Sitting in Ramesh’s room five minutes later, and thinking over the day’s events, I realized the truth of this.

“We shouldn’t have counted our chickens before they were hatched, like the proverb says,” I told my friend, shaking my head wisely.

“Shut up,” said Ramesh.

I was about to give a heated reply to this, when I noticed that Ramesh’s thoughts were elsewhere. He had taken out the envelope from the secret drawer and was staring at it in a peculiar manner.

“What’s up?” I asked curiously. Ramesh looked at me. The glint in his spectacles told me that my friend’s curiosity was once again working overtime. “Have you ever stopped to wonder,” he asked me slowly, “why the envelope was hidden in the secret drawer in the first place?”

I was ready for this. “Well, it’s obvious that the person who hid the envelope must have thought the stamp was valuable, the same as we did.”

But Ramesh was not to be put off so easily. “I’m not so sure…,” he said thoughtfully. He looked down at the envelope in his hand. “Even if that person thought the stamp was valuable, then why hide it? Why not sell it, or stick it in a stamp album? Why hide it?”

He had me there. I had no ready answer.

Ramesh, whose suspicions were growing like flowers in spring, carefully put down the envelope and, from a nearby drawer, took out a magnifying glass. “There must be something special about the envelope that makes it valuable enough to hide,” he explained to me. “I’m going to find out what it is,” he continued determinedly.

I walked over to where Ramesh was sitting and stood behind him. Ramesh picked up the envelope again and, as I stared over his shoulder, he began to go over it once more, inch by inch. “I’m convinced,” he told me, “that somehow we’ve been missing something that’s been staring us in the face all the time.” The fiasco of the Sirijpur ‘Royal Head’ had evidently not dampened Ramesh’s habitual curiosity.

Together, we attempted – unsuccessfully – to decipher the illegible address on the envelope… Ramesh examined the address under the magnifying glass… he put his magnifying glass over the postmark and the stamp.

Then Ramesh suddenly snapped his fingers.

He sprang up from his chair, with the alacrity of a leopard that had sat down on an anthill by mistake, clutching the envelope in his hand, his head nearly crashing into my jaw. “We’re going to the kitchen,” he told me briefly, and was out of the room before I could react to this startling announcement.

By the time I had made my way to the kitchen, considerably puzzled by Ramesh’s strange behaviour, my friend had already put a kettle of water on to boil. The strain had evidently been too much for him. “I – I don’t think I’ll have any tea, thank you,” I told him politely, having read somewhere that the best way to deal with lunatics is to humour them.

Ramesh gave no reply. He waited impatiently, his face flushed, until the kettle began to boil. Then slowly lifting his hand, he held the envelope in the steam and very carefully peeled off the stamp.

He uttered a shout of triumph.

With one bound, I was at Ramesh’s side. My friend was staring down at the back of the stamp he had just peeled off. I too stared at the back of the stamp. And as I did so, my head began to swim. A message, in closely-packed, microscopic handwriting, had been hidden under the stamp!

I blinked, half expecting the words to disappear. They didn’t. Ramesh sat down on a nearby stool and studied the message under his magnifying glass. Then he gave a low whistle. “I wonder what my father will have to say about this…,” he said slowly.

Ramesh’s father had a lot to say about the discovery. In fact, after only one glance at the message through Ramesh’s magnifying glass, he became so excited that he immediately called over some scholar friends of his to have a look at the find. They confirmed the great value of the discovery. What Ramesh had discovered at the back of the stamp was a secret message sent by the British Political Resident of Sirijpur State to his colleague in the neighbouring Princely State at the end of the nineteenth century. The message shed new light on involvement of the then colonial British rulers of India in the affair of the then Raja (King) of Sirijpur, who gave up his throne in favour of his nephew in 1899. Although the British were suspected of having put pressure on the Raja (who they felt had ties with Indian feedom fighters) to abdicate, no proof of this was ever found. The secret message Ramesh had discovered was the first concrete evidence of their involvement. It thus had great historical and antique value.

Not long after, a museum bought the envelope and stamp, paying a lot of money for it. Ramesh insisted on sharing the money with me, since I had contributed towards buying the miniature chest-of-drawers which started it all. Nevertheless, it was only due to Ramesh’s great curiosity that the discovery was made. And Ramesh, true to form, is still not content. He now wants to find out how the envelope came to be hidden in the miniature chest-of-drawers in the first place.

We are planning to re-visit the junk shop!