Part I: Joining the Pujas

Part I: Joining the Pujas“My dear Sharma moshoi! Welcome, welcome!” The worlds were spoken in Bengali-accented English with which Ramesh and I, though we had been in Kolkata for only four days, had already become familiar.

“Good morning, Mr. Mukherjee,” replied Ramesh’s uncle. “Meet my nephew and his friend.”

We were all standing on the steps leading up to Mr. Mukherjee’s ancestral house on Kolkata’s S.N Banerjee Road. The Mukherjee mansion was fronted by a row of shops but the huge entrance stood out prominently. Mr. Mukherjee, a middle-aged gentleman dressed in a white silk kurta and dhoti (the traditional Bengali dress favoured by men), was an office colleague of Ramesh’s uncle.

“Welcome boys, welcome!” beamed Mr. Mukherjee. “Come, have a darshan of Goddess Durga Ma!”

We followed our host, who had generously invited us to join his family in the annual Durga Puja festival celebrations in the Mukherjee joint family mansion, through the entrance and a narrow corridor and suddenly found ourselves standing in a huge hall. I instinctively looked up and saw that the hall extended right up the entire middle of the building, and its ceiling was three storeys above our heads. The first and second floors were bounded by railings over which people were leaning and gazing down. I lowered my eyes to see what they were gazing at. They were watching a raised marble platform at one end of the hall on which were placed five larger-than-life idols. The hall itself was crowded with people. Everybody was dressed in new clothes, and the women wore lots of jewellery. Mr. Mukherjee gestured in their direction.

“All my relatives are here today!” he declared proudly. “No matter where they are, in this country or even outside, in foreign lands, they always come home in October, during Durga Puja!”

I saw a boy of about my age detach himself from a group of people and come towards us. Mr. Mukherjee introduced him.

“Meet my son, Niranjan,” he said. “Niranjan, I leave these boys in your care.” And, so saying, he led Ramesh’s uncle towards a group of men a little further off.

“We’ve never participated in Durga Puja celebrations before,” I told Niranjan. “This is our first visit to Kolkata. It sure was kind of your father to ask Ramesh’s uncle to bring us over!”

“I am glad you’re here,” said Niranjan, smiling.

Ramesh looked about him. “Who do those idols represent, Niranjan?” he asked.

“In the centre, standing on a lion, her ten arms holding different weapons, is Goddess Durga,” replied Niranjan. “She’s thrusting her spear into the evil king of the demons, who had been terrorizing the earth. To her right is Lakshmi, the Goddess of wealth and beyond her, with the elephant-head, is Ganesh, the patron God of businessmen. To Durga’s left is Saraswati, Goddess of learning and beyond her, Kartikey, the handsome God who represents beauty. All four, as Bengali mythology has it, are the children of the mother Goddess Durga.”

“How long has your family been celebrating Durga Puja in this house?” I asked Niranjan.

“Oh, for over a century!” replied Niranjan, a touch of pride in his voice.

Ramesh suddenly looked interested. “You mean this house is actually that old?” he asked.

Niranjan smiled. “Older,” he said. “This house was built around one hundred and seventy years ago!”

Ramesh’s spectacles began to glint excitedly. “Why, then this house is-is historical!” he exclaimed. “I’ve never been inside a house as old as this!” He looked at Niranjan and his eyes were almost pleading. “Could we explore the house a bit?” he asked.

I was shocked. “How can you make such a request, Ramesh!” I exclaimed terribly embarrassed by my friend’s presumptuousness. “You can’t go ferreting around somebody’s house as if it’s a tourist attraction!”

But, Ramesh, as usual, ignored my wet blanket treatment. He continued to look pleadingly at Niranjan.

“I’m flattered you find my house so interesting,” said Niranjan, smiling broadly. “I don’t think we’ll disturb anybody. They’re all down here watching the morning puja (prayer). Come along!”

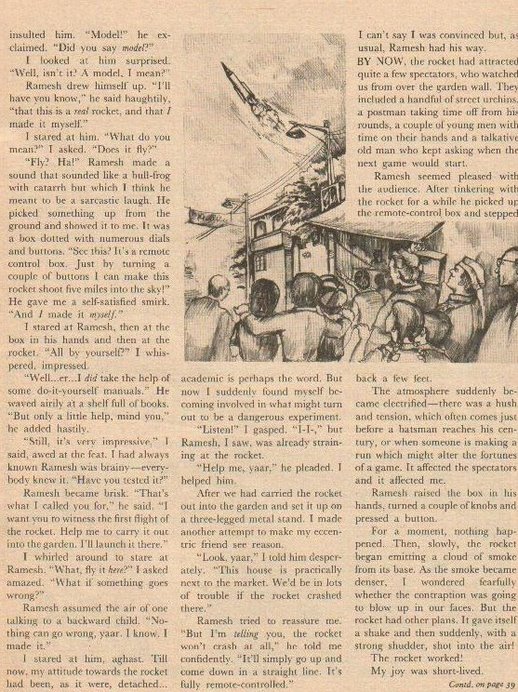

I hesitated. My eyes wandered to the marble platform on which two priests sat, in front of the idols surrounded by huge plates full of fruits, sweets, gifts and offerings. The air was heavy with incense. Four drummers stood in front of the platform and beat a rapid-fire hypnotic rhythm. They were accompanied by the beating of gongs.

“Er…won’t they be serving Prasad soon?” I asked Niranjan, my eyes lingering longingly on the plates of fruits and sweets, which were being symbolically offered to the gods and would then be distributed amongst the worshippers after the morning puja (prayer) was over. “I think the puja is about to finish…”

Ramesh made a face. “Now, don’t be a greedy hog, yaar!” he exclaimed loudly, making heads turn and me blush with embarrassment. “The Prasad won’t run away!”

“Don’t worry!” grinned Niranjan. “I’ll make it a quick tour.”

We followed Niranjan up a huge marble staircase. On reaching the first floor, he turned into a large doorway.

We found ourselves standing inside a massive, high-ceilinged room. A gigantic chandelier hung from the ceiling in the exact centre of the room. Beautiful furniture, clearly of great antique value, was neatly arranged around the room. The walls were adorned with paintings and family portraits.

“Our drawing room!” announced Niranjan. “This is the room where we receive and entertain guests and family members gather together. Some of the furniture dates back to the last century!”

Ramesh whistled as he gazed around him. “This room was certainly built for a big family!” he exclaimed.

“Yes. We have lots of relatives, and they all made it a point to attend this Durga Puja.” Niranjan’s expression became sad. “It’s probably the last Durga Puja we’re going to celebrate in this house!”

Ramesh looked quickly at Niranjan. “What do you mean?” he asked.

Niranjan smiled wryly. “It’s a pretty expensive affair, you know,” he said. “And the family doesn’t have much money left. High taxes and increasing costs have eaten into the ancestral property. And my father certainly can’t afford to host such a festival on only his salary!”

“It’ll be a great pity if this family custom ends now!” I observed.

“I don’t think we’ve much choice in the matter,” murmured Niranjan softly. He quickly shook himself. “Anyway, we’re certainly celebrating this Durga Puja in style! Come on, let me show you the next room, now! If we don’t hurry through this tour, our friend here will miss his Prasad!”

The room Niranjan next took us to was clearly a library. It was a vast room with shelves filled with books lining all walls. Most of the shelves were dusty and the books looked old and little used.

Ramesh darted forward eagerly. He had the air of an archeologist who had just discovered another Mohen-jo-daro, India’s oldest excavation site. As he paused before a bookcase whose contents were coated with a layer of dust an inch thick, he uttered a noise that sounded like glue pouring out of a jug.

I recognized the symptoms. Sure enough, an excited Ramesh turned a pleading face to Niranjan. “Could I have a look at some of these old books?” he asked. “They don’t seem to have been touched for years and years! Maybe there’s a very valuable book lying forgotten in one of these shelves!”

Niranjan hesitated for only a moment. “Go ahead!” he replied. “It won’t harm the books to get a little dusting!”

The sound of the drums and gongs, which had been following us wherever we went, ceased abruptly. I looked at Niranjan. “Er…has the morning puja come to an end?” I asked meaningfully.

Niranjan smiled. “Yes,” he replied. “Should we go down?”

I nearly licked my lips. “Yes let’s do that!” I said, happy that Niranjan was so understanding.

We left Ramesh in the library and hurried down to the hall. When we returned, armed with packets of prasad, we found Ramesh sitting in front of a table piled high with books. He was holding a small wooden box. He looked up when we entered, his face flushed with excitement.

“Look what I’ve found in one corner of a bookcase!” exclaimed Ramesh, holding up the box.

“What’s inside?” asked Niranjan, interested.

“This!” announced Ramesh, and, in the manner of a conjurer pulling a rabbit out of his hat, he opened the box and carefully drew out a rolled up paper. Putting the box on his lap, he slowly unrolled the piece of yellowing paper then handed it to Niranjan. I craned my neck to look.

There were only four lines of thin, spidery writing, very faint. I couldn’t understand it, but knew the script was Bengali.

“It looks like a small poem,” said Niranjan slowly. “I’ve absolutely no idea who could have written it!”

“What does it say?” asked Ramesh quickly.

“Well, I’m not good at translating poems from Bengali to English,” replied Niranjan apologetically. “But I’ll try to give you the meaning of each line.” He raised the piece of paper closer to his face and peered intently at the words. “This is how it goes: ‘Neither summer nor winter…Mother has come home…beneath the peacock…number the petals…”

There was a brief silence.

“Sounds Greek to me,” I said, trying to be witty.

Ramesh ignored me. His brow had ceased into a puzzled frown. “Why has this poem been preserved like this in this box?” he asked Niranjan.

“I’ve no idea,” replied our host. “This is the first time I’ve seen this paper or the box. I don’t think my father knows about them, either!”

“You mean, there’s no way we can find out who wrote this poem and why it’s been preserved?” asked Ramesh, sounding very disappointed.

Niranjan scratched his head. “Well, perhaps my dadu – my grandfather - knows something about it,” he said hesitatingly. “Since the puja is over, he must have come upstairs and gone to his room. We can go and ask him.”

Ramesh jumped to his feet as if a spring had just been released beneath him. “That’s a good idea!” he exclaimed. “Let’s go!”

“Hey, hold it, yaar!” I cried agitatedly. “When are we going to eat the prasad?”

“Later, later,” said Ramesh impatiently.

“All right, let’s go” agreed Niranjan, handing the yellow paper back to Ramesh to roll up and replace inside the box.

We hurried out of the library. Niranjan led us down a long corridor and stopped before a small door. He knocked.

“Who is it?” We heard a soft voice from behind the door.

“Dadu, it’s me,” replied Niranjan. “My friends would like to meet you.”

“Come in,” invited the soft voice.

We obeyed and found ourselves standing in a small room sparingly furnished with a bed, a desk and some chairs. On one of the chairs, by the window, sat an old man. He smiled at us.

“Welcome, boys,” said Niranjan’s grandfather. “I hope you are enjoying Durga Puja.”

“Yes, sir, we are,” replied Ramesh. He opened the box in his hands and took out the piece of paper. “We just discovered this in the library,” he said, handing the paper to Niranjan’s grandfather.

Niranjan’s grandfather unrolled the paper and ran his eyes over the words written on it. And, as he did so, his face brightened.

“I’d almost forgotten about this poem,” he murmered softly.

“Do you know who wrote it, Dadu?” asked Niranjan.

Nirnjan’s grandfather looked up. “Yes,” he replied. “My grandfather – your great-great-grandfather – wrote it. As far as I know, it’s the only poem he ever wrote. It was found amongst his possessions after he had died. The handwriting is his. It was preserved, as were all his other possessions, because, as you know, your great-great-grandfather is a family hero!”

Ramesh’s head jerked up. He looked like an infant who’s suddenly spotted an ice cream parlour. “Was your great-great-grandfather a freedom fighter or something?” he asked Niranjan.

Niranjan smiled proudly. “Well, he was one of the few who stood up to Lord Curzon, the Viceroy of that time!” He looked at his grandfather. “Dadu, isn’t there a story about hidden treasure connected with my great-great-grandfather?” he asked.

Niranjan’s grandfather looked thoughtful. “Well, yes there is a story,” he replied slowly.

Ramesh could hardly control his excitement. “Please tell us the story,” he implored.

Niranjan’s grandfather smiled. “All right!” he said. “I’ll tell you.” He shifted slightly in his seat and then began: “As you must have studied in your history books, in 1905 the then British Viceroy, Lord Curzon, virtually the British ruler of India, initiated a move to partition the state of Bengal, which was the seat of Indian Nationalism and anti British agitation in those days. Well, this sparked off a big agitation against the move in which my family played an active part. Word spread that the British were planning to arrest the male members of our family. So it was decided that the whole family should leave the city for a time and lie low in a house they had near Siliguri in North Bengal. The story goes that, before leaving, my grandfather – Niranjan’s great-great-grandfather – who was the head of the family then, hid some of the family wealth in order to safeguard it from possible looters. Unfortunately, he died before the family could return to Kolkata after things had quietened down and so nobody knows where he had hidden the treasure – if, at all, he did hide any such treasure in the first place!”

All through the narrative Ramesh had been sitting on the edge of his chair, tensely clasping and unclasping his hands. Now he exclaimed: “You mean that, at this very moment, there’s a treasure trove hidden somewhere in this house?”

Niranjan’s grandfather smiled. “I didn’t say that,” he replied. “Nobody knows whether the story is true or not!”

At that moment, the sound of a gong reached our ears.

“Ah!” exclaimed Niranjan. “The mid-day bhog (festival lunch) will be served now.” He looked at me and grinned. “I think you’ll find it delicious!”

I hastily got to my feet. “…Then, shouldn’t we go and…participate?” I indicated the packets of Prasad I was still holding in my hands. “We haven’t eaten anything since morning.”

Yes, you boys go downstairs and have your bhog,” agreed Niranjan’s grandfather.

The bhog (the special festival lunch which is served to all worshippers and guests during all the five days of the Durga Puja celebrations) was indeed, delicious. It was a mixture of rice, dal (lentils) and vegetables. Niranjan kept referring to it as khichri. It was followed by paish, a very sweet rice pudding. I ate heartily.

Ramesh, however, barely touched his food. He lingered over the khichri in an absent-minded sort of way and looked too preoccupied to pay much attention to the paish. Suddenly, towards the end of the meal, his head shot up with a jerk. He grabbed my arm, nearly causing me to drop my spoonful of sweet rice over my shirt.

“Hey! Watch it!” I exclaimed.

“Listen!” cried Ramesh breathlessly, his spectacles beginning to glint. “I’ve just got an idea about that treasure!” He turned to Niranjan. "I think your great-great-grandfather may have left a clue to the treasure!"

End of Part I

Next Part: The Clue